Providing adequate housing

for all

The unprecedented economic and social crisis caused by COVID-19 poses a disproportionate threat to those deprived of dignified, adequate housing. This includes people facing homelessness, living in overcrowded housing, or risking eviction, victims of domestic violence, women and gender diverse people disproportionally impacted by loss of income during covid, and refugees and asylum seekers facing discrimination in access to housing.

Released in 2020, the 5th Overview of Housing Exclusion in Europe by FEANTSA and the Foundation Abbé Pierre reports at least 700 000 people sleeping rough or in emergency or temporary accommodation on any one night in the European Union, already before the pandemic, namely 70% more than a decade before. The Overview also shows that asylum seekers and people under international protection face higher levels of homelessness than other vulnerable groups because of the failing welcome system in Europe.

Financial inaccessibility, competitiveness and discrimination – characteristics of housing markets across the European Union – prevent many people from accessing adequate housing, with some having no choice than to turn to the black market, makeshift homes, or the streets.

Key figures

Setting the scene

Official figures show one in ten EU households spent over 40% of their income on housing costs in 2018, 15.5% of households lived in overcrowded conditions, 13.9% lived in damp housing, and 4% experienced severe housing deprivation. In short, unfit housing conditions remain a harsh reality, particularly in Eastern European countries. Moreover, with an income gap of 16% and a pension gap of over 30% between women and men, the housing crisis has a female face – as Michaela Kauer, Coordinator of the EU Urban Agenda Housing Partnership, described at the 2020 European Week of Regions and Cities.

Poor households are eight times more likely to be overburdened by housing costs than non-poor households – and the pandemic has exacerbated these conditions. Children are particularly vulnerable to housing exclusion: at EU level, the overcrowding rate is higher for households with children (21.9%) compared to the general population (15.5%). People with an activity limitation, especially young people, are more likely to be overburdened by housing costs and to experience severe housing deprivation. Meanwhile, Europe’s inadequate reception and unsuitable accommodation systems for migrant populations put asylum seekers at a greater risk of experiencing homelessness.

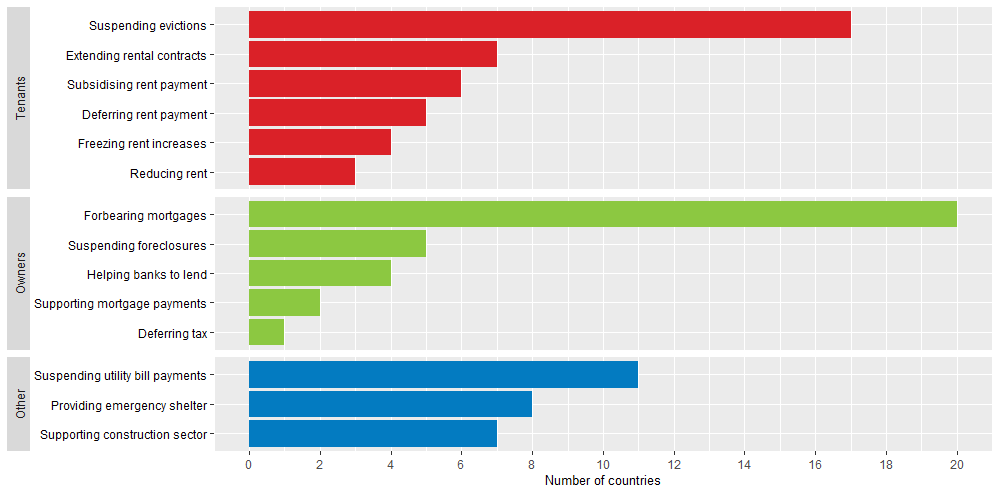

In the context of the public health crisis, many public authorities have taken exceptional measures to protect vulnerable people, both in rental and homeownership sectors: these include moratoria on rental payments, bans on evictions, protection of tenants in rental housing, mortgage payment referrals, temporary accommodation for people experiencing homelessness, suspending disconnections from utilities or discounting utility bills et al. For example, in Barcelona rent moratorium was established for properties owned by the Barcelona Municipal Housing and Rehabilitation institute. In Nantes (FR) financial support has been provided for low-income tenants through a housing solidarity fund.

Some of these progressive measures had been recommended for years, and the pandemic made them possible in a short time. As matter of fact, the health crisis has created a precedent, demonstrating that when the political will and resources are mobilised, housing can be secured and homelessness can be ended.

However, when these emergency measures are lifted, a sudden rise is expected in the number of people at risk of eviction, leading to a surge in homeless numbers. The challenge now for public authorities is to turn recent improvements into long-term policies, as FEANTSA called for in its 2020 #hotelstohomes campaign. Plans to keep homelessness down in the future have been announced by national, regional and city authorities. In the UK for instance, Liverpool developed a GBP 1.4 billion recovery plan, which includes the development of more than 200 new modular homes and community centres. Four thousand homes will also be renovated for vulnerable households in the most deprived neighbourhoods, which are also most at risk from COVID-19. This work is estimated to create 25 600 jobs, 12 000 of them in construction, as highlighted in an OECD presentation at the European Week of Regions and Cities. The European Investment Bank (EIB) announced in February 2021 the approval of EUR 5.3 billion to strengthen investment in public services, EUR 1.8 billion of which is for urban services including social housing. The EIB board agreed to back sustainable urban investment in Greece and Poland and financing for social and affordable housing in the Italian region of Lombardy and across Spain. While the recovery package offers opportunities for further investments in the housing sector, the question remains as to how countries will spend these funds to secure adequate and accessible housing, especially for the most vulnerable.

Source: OECD (2020), Housing Amid COVID-19: Policy Responses and Challenges.

Inspiring case studies

These examples of cities looking for innovative strategies to ensure no-one is left behind are selected from UIA projects and URBACT networks, and from other experiences shared during the ‘Cities engaging in the right to housing’ initiative.

Ghent

Aiming for zero homelessness and affordable housing for all

Ghent leads the URBACT ROOF network of nine EU cities working together to eradicate homelessness using the ‘Housing First’ model. Ghent is also active on migration inclusion, and its local project ‘Refugee Solidarity, ‘a pro-active approach for welcoming refugees, starting the integration process from day one’ has been labelled good practice by URBACT.

Last but not least, Ghent is active in UIA with the project ICCARus employing a revolving fund to provide affordable housing units to low-income groups.

Athens

From assistance to independent living

Through UIA, the City of Athens piloted an inclusion project called Curing the Limbo from 2018 to 2021, targeting refugees who had been granted asylum in Greece.

With the support of several actors, among which the Catholic Relief services responsible for housing, the project developed an affordable housing model to assist refugees in the transition from temporary emergency assistance solutions to independent living in Athens.

The goal was to create a sustainable housing model that fits the characteristics of the Athenian housing markets, encouraging landlords to join the project. For this purpose, the project created a housing facilitation unit based on a social rental agency which provides a range of services.

These include: access to a pool of available apartments; rental technical support helping tenants understand contract clauses, leases, electricity bills etc; conditional cash subsidies for a limited period; legal support to renters and owners; and more.

Lyon Métropole

Housing towards empowerment

Lyon, a city active in the debate about adequate and affordable housing (hosting the International Social Housing Festival in 2019), has launched an ambitious, innovative ‘Housing toward empowerment’ project with UIA support.

Home Silk Road puts vulnerable groups at the centre of a project to renovate a historical building. It aims to create a hub for several cultural and economic activities, including housing and non housing-business partners.

Odense

Implementing Housing First since 2009

Odense, a city of less than 200 000 inhabitants, is also part of the URBACT ROOF network. It has experience in implementing Housing First since 2009, when it was selected as one of the eight cities to participate in Denmark’s national homeless strategy launched the same year. In 2019, the municipality of Odense, together with housing-related associations, issued a housing guarantee for homeless people, ensuring that any homeless citizen in Odense should not have to wait more than three months for a home.

Key takeaways

Reflexions over the course of the URBACT-UIA ‘Cities engaging in the right to housing’ initiative explored the role of city administrations and the root-causes of housing exclusion.

As a result, key actions governments and other bodies can take to help ensure no-one is left behind are briefly summarised here:

- Protecting tenants from being evicted should be a priority for all levels of government, continuing exceptional measures to support the right to housing after the COVID-19 health crisis (cr. April 2020 UN COVID-19 Guidance Note on Prohibition of evictions and the Zero eviction campaign et al).

- End homelessness by 2030, in line with the UN Sustainable Development Agenda and the European Pillar of Social Rights, while building mechanisms to monitor homelessness and homelessness policies across the EU;

- Mobilise EU recovery funds and other EU funding opportunities to support the Housing First scale-up; involve governments to invest more on good quality public social housing, adopting measures for security of tenure, rent stabilisation and control, reuse of vacant buildings, and curbing energy poverty in renovation.

- Cities should involve stakeholders in public housing programmes and measures that expose, stop and prevent racial and gender-based discrimination, and criminalisation of public housing residents.

- The current failures of asylum and immigration policies must be addressed as part of the fight against homelessness and housing inequalities.